Foulness Churchend Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan

7. Character Appraisal

Spatial Analysis

7.1 The military road provides a modern framework for the village, approaching it from the south before turning east opposite the pub with a subsidiary route branching west. The conservation area boundary is loosely drawn around the village, the settlement having no clearly defined edge, using old watercourses, ditches, tracks and rear property boundaries.

7.2 The spinal military road passes through expansive flat marshlands and arable fields dotted with occasional isolated farmsteads and military buildings before reaching Churchend. Distant views of the church tower at Churchend rising above trees and scrub indicate the presence of the village. The road marches dead straight towards the village, taking on a gentle and more deferential route through the historic settlement before continuing eastwards. The curve of the road makes an important contribution to the informality of the area (Fig. 9). Neat pairs of white semi-detached weatherboarded cottages announce the village. They are set in a regular arrangement with an even building line, but set back in generous plots with low front boundaries or open to the street so that there is little sense of enclosure. Wide green verges border the road, contributing to the rural character of the village, and a historic grassy track known as Turtle Wall leads away to the south east (Fig. 10).

7.3 Further north brick and weatherboard cottages line the road behind front gardens and verges on the east side until the scene opens up at Old Hall Farm by a water-filled ditch. Here the landscape opens out with expansive views to arable land between unenclosed farm buildings that generally run perpendicular to the road (Figs 11, 12). To the west the arrangement is informal with occasional properties, some barely visible behind trees and scrub, and wide verges. A broad green open space provides views west where an unenclosed cart track heads towards the sewage treatment works.

7.4 Trees narrow the view looking north along the road towards a grassed traffic island where the main road turns east at some yellow brick cottages with the secondary route branching west (Fig. 13). This marks the historic core of the village. Here the view opens up with the wide road junction and village green. The scene is dominated by the attractive white weatherboard façade of the George and Dragon public house, a landmark building in the village. Adjacent to this a gravelled car park in front of the shop contributes to a spacious quality. The village green is a broad, loosely defined grassed area edged by low trees and scrub along its northern and eastern boundaries. The green has an open setting with agricultural fields to the north. The shingled spire and multiple gables of the church are important features in the scene, with churchyard trees contributing to the green setting (Fig. 14). The village green provides a vital central amenity space not just for the villagers but for the island as a whole.

Fig. 14 View across the village green looking west, with the George and Dragon and shop to the left.

7.5 As the main road turns eastwards at the village green it deviates from the route of the old byway which still exists alongside it as a wide grass verge with occasional trees (Fig. 15). Yellow stock brick semi-detached cottages on the north side of the road are set back in attractive gardens, with an open plot between. An unenclosed track heads off behind these cottages from the road along the field edge leading to other properties to the rear. The irregular positioning of properties and large plots contribute to the informal rural character of the conservation area. As the road leaves the village to the east, the conservation area takes in a poorly maintained gravelled parking area with recycling bins. Behind this is the village hall, a dilapidated building excluded from the conservation area and set in an open, unkempt plot. These spaces do little to enhance the attractive appearance of the conservation area. The old byway that once led on to the parish workhouse is a historic route that continues eastwards away from the village hall.

7.6 Where the road branches west the low brick boundary wall of a pretty listed walled garden in front of the George and Dragon pub backs the footway. This wall is an important and prominent boundary feature, with a picturesque view across the garden to the pub. The wall continues past the churchyard and where it ends the boundary is defined by a low hedge marking a more recent extension to the churchyard (Fig. 17). As the road continues west out of the village the landscape setting opens up again with views across arable fields to the south. The long brick school building marks the western edge of the village and of the conservation area (Fig. 16). This building, now an excellent heritage centre, is set far back behind attractive gardens on an old track that heads off to the north towards Nase Wick. The old school playing field that is concealed behind tall conifers provides parking for the heritage centre.

Character Analysis

7.8 The existing built environment of Churchend village comprises an irregular arrangement of properties derived from a series of phases of development over several centuries, with 1920s development to the south taking on a regular but open settlement pattern. The medieval origins based on the church and manor provide the historic focus for the village, now reflected in the informal arrangement of mostly 19th century buildings close to the village green, including the church, rectory and Old Hall farmhouse. Few buildings remain from 17th century infilling that resulted from population increase. Early buildings were timber framed, although few of these survive in the village today. Most were swept away during subsequent phases of redevelopment. The George and Dragon is a notable exception and an important survival from this early phase. Soft red brick was introduced by the 18th century, and although it is not a dominant material today it can still be seen in places. Extensive rebuilding in the mid-19th century introduced yellow stock brick, and a good survival of buildings from this date reflect reforms and improvements made during that period, notably under the patronage of George Finch, who owned the manor from 1826. Finch provided funds towards the rebuilding of the church and the rectory, and for the school. The village extended southwards at this time, and some of the Victorian development survives, notably the weatherboarded Kents Cottages. The outbuilding at 4a Churchend may provide evidence of the former industrial complex that existed around the old windmill. The principal linear development to the south that exists today derives from the intervention of the War Department with the regular arrangement of mainly residential properties in the form of brick or weatherboarded cottages built to address the new spinal road in the 1920s.The village was further shaped under military ownership by the demolition of some older properties, including the old windmill, workhouse cottages and school cottages.

7.9 Despite the organised rebuilding programme undertaken by the War Department after the First War, the result is not overly formal and rigid, with the older historic settlement form still evident. The design of the buildings was simple and modest, with properties set back in large plots with gardens. A mixed but limited range of materials was used, including stock brick, weatherboard, and a mixture of plain clay tiles and slate roofs. This contributes to the pleasing visual character of the village, whilst also offering a degree of cohesion.

7.10 The conservation area exhibits a variety of architectural styles and forms that reflect these various stages of its evolution and that contribute to the character of the streetscape. Simplicity and restraint in design and scale are characteristic, and there are few decorative embellishments. The predominant building type is the modest semi-detached two-storey cottage of the1920s, rectangular in plan, with simple hipped roofs. However other buildings that have played an important role in the life of the community add architectural and historic interest and contribute to the texture and variety of the conservation area.

Materials and detailing

7.11 The conservation area exhibits a varied but limited range of materials that are an important characteristic of local distinctiveness. Brick is much in evidence, principally yellow stock brick from the Shoeburyness brick fields used from the mid-19th century and laid in Flemish bond or stretcher bond (although an older farm building displays areas of English bond). Occasionally earlier soft red bricks can be seen (Fig. 18). Weatherboard is the other dominant exterior wall treatment, and is generally painted white on front elevations and black to the side, although historic photographs suggest that this is a relatively recent approach, with tar a more likely historic finish. There are a small number of rendered buildings painted white, including the Old Hall and agricultural outbuilding by the village green.

Fig. 18 Local soft red and yellow stock brick, laid predominantly in English bond, on old farm building.

7.12 Traditional roofing materials are either slate or plain clay tiles. Historic photos show that clay pantiles were also used. Slate roofs sometimes have red ridge tiles. Roofs are pitched and gabled or hipped at around a 45˚ pitch, and are sometimes gently canted towards the eaves. Rooflines are simple and dormers are absent.

7.13 The traditional fenestration consists of small paned vertically sliding sashes, eight over eight or six over six being common. In brick buildings windows have flat or shallow segmental arched window heads. Pentice boards are used where there is weatherboarding. Small paned casements are also seen. Timber window joinery is generally painted white or black. There appear to be few historic doors that have survived, although there are some older part-glazed doors with small panes, and some examples of vertically boarded doors that have survived on Kents Cottages. Doors may be located to the front or the side, and are sometimes sheltered under small mono-pitched porches or beneath flat canopies on brackets (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19 Small paned casements and sash windows, traditional door with simple canopy, no.18 Churchend.

7.14 Traditional domestic front boundary treatments are generally of a type appropriate to a rural setting, with low timber post and rail fences, picket fences and hedges being common traditional forms. Vari-coloured walls of local brick in Flemish bond are also a feature, particularly for higher status properties such as the church, the rectory, and Old Hall farmhouse, as well as the walled garden to the front of the pub.

Individual contributions to character

7.15 The George and Dragon is a landmark building at the heart of the village, with its prominent white weatherboarded façade, small paned sashes, hipped grey slate roof and distinctive ridge tiles (Fig. 20). It is believed to have originally been constructed in the early 17th century. Philip Benton, writing in 1867, notes that it was once two cottages, but was converted to a pub in the late 17th century. As well as the strong visual contribution it makes to the street scene, the pub has an important place in the social and cultural history of the village, not least because of its dubious association with bare-fist fighting. Fights took place in the walled garden in front of the pub, and local legend has it that the high wall between the churchyard and the garden was put up at the request of a reforming vicar so that the congregation could not see these bloody contests. The pub is Grade II listed, as is the 18th century walled garden. The wall of the garden is constructed of vari-coloured local brick. Adjoining the garden and at right angles to the pub is a small single storey pitched roofed brick building with recessed sash windows and a single chimney. It has a mid-19th century appearance, and may have been a wash house or a brew house.

7.16 The garden wall continues along the footpath edge to the churchyard, which is entered through iron gates. The parish church is Grade II listed, and was built around 1853 in an Early English style to the designs of William Hambley (Fig. 21). It is constructed of roughly squared grey Kentish Ragstone rubble with stone dressings. A distinctive feature of the church is the range of three steeply pitched grey slate roofs, gabled to east and west. The south tower with its octagonal shingle tower hipped at the base has a noticeable lean. The tower is an important landmark in the flat landscape, marking the location of the village in distant views. The churchyard is partly owned by the Parish Council, and contains a good survival of early gravestones and associated ironwork. A well-cared for war memorial is a feature near the entrance. A number of gravestones are Grade II listed, including the earliest in the churchyard, a headstone memorial for Jonas Allen, dated 1698. The churchyard encompasses the site of the previous timber church, unmarked as such but indicated by the monuments to the rectors Thompson, Ellwood and Archer that, according to Benton12, once lay within its walls. The churchyard is mostly laid to grass, and is well maintained with mature trees and hedges. The churchyard has been extended in recent years as the old yard became full, which had prompted fears that in the future interment would have to take place on the mainland. The extension is an open grassed area bordered by hedgerow that would benefit from some further tree planting in keeping with the more historic churchyard in order to soften the landscape.

7.17 Opposite the church lies the Old Rectory, and this remains church property. It is an elegant stock brick building of 1846, with a shallow hipped grey slate roof and small paned hornless sashes, but with remnants of an earlier late 17th or early 18th century building (Fig. 22). The back kitchen was rebuilt in 1793 and survived the 19th century rebuild. The house and grounds are given privacy by the surrounding high boundary wall and trees growing within the grounds as well as outside. The wall is constructed of vari-coloured brickwork, including soft red bricks likely to be from the earlier phase of construction as well as 19th century local stock bricks. The Old Rectory is Grade II listed.

Fig. 22 The Old Rectory, photographed from within the grounds.

Reproduced with kind permission of R.W. Crump.

7.18 On the east side of the spinal road at 10-14 Churchend are Kents Cottages, a picturesque Grade II listed terrace of white weatherboarded mid-19th century timber framed cottages with a later addition of a cross wing (Fig. 23). This is an important survival of vernacular timber-framed cottages, where many were demolished and rebuilt by the War Department as part of the improvements in the 1920s. They have grey slate roofs with red ridge tiles, with a decorative bargeboard on the cross wing gable. The front entrances have small open fronted and weatherboarded mono-pitch porches with corrugated roofs, and there are small paned sash windows with black painted joinery.

Contribution of unlisted buildings

7.19 There are a number of unlisted buildings within the conservation area which make an important contribution to its special character, generally relating to 19th century improvements or to the 1920s rebuilding programme. Many of these were formerly on the Rochford District Council Local List of Buildings of Architectural, Historic and Townscape Importance, and the Local Plan included a specific policy with regard to protecting these buildings. The replacement plan contains no such provision and these buildings are vulnerable to change. All the buildings described in 6.19 to 6.28 were previously on the Local List.

7.20 The old school and schoolhouse which mark the western extremity of the conservation area are an important survival from the Victorian improvements (Fig. 24). The school has a special significance in the social history of the community, and reflects a time when the island was more populous than it is today. Constructed of local yellow stock brick widely used in the village at the time, the building reinforces the character derived from the local palette of materials, but has a distinct building form related to its use, with a long low pitched roof range and hipped roof cross wing. Although the arrangement of window openings is original, the windows themselves were replaced with a more modern glazing pattern some time ago. The school playground is still extant, along with some of the outbuildings, retaining evidence of former use. A pair of cottages that once stood alongside the school was demolished soon after WWII. Whilst the school building used as a heritage centre is MoD property, the school house remains that of Essex County Council.

7.21 An interesting group of buildings associated with the manor and the farm are located along a driveway opposite the village green. These include the Old Hall farmhouse, adjacent weatherboarded cottage and a disused agricultural building at the entrance to the drive. The Old Hall is a white rendered building of around 1850, with a south facing front façade looking onto farmland over a low brick boundary garden wall (Fig. 25). In the context of the other domestic architecture of the village the façade is imposing, indicating its status as the manor house at which courts were held until the War Department took over the manor in 1915.The front elevation retains its symmetry but has had some unsympathetic alterations, including reroofing in modern interlocking tiles. There are UPVC sashes in recessed window openings, and a later mono-pitched glazed porch between the ground floor windows. The house is well set back from the public road and barely visible behind trees. The adjacent cottage is believed to be 19th century in date but much altered, built to provide accommodation for farm workers (Fig. 26). The cottage has been renovated and has a weatherboarded exterior in keeping with the vernacular traditions of the village, with a more recent clay interlocking tiled roof and some plastic windows. The side elevation of the cottage is visible through trees from the main road. The definitive map of Essex shows a public footpath passing along the driveway past these buildings but this is not signposted or maintained.

7.22 The agricultural outbuilding on the driveway is a prominent feature in the streetscape from the public road and from the village green, and is also clearly visible when viewed from the approach road into the village from the west (Fig. 27). The main range is a high single storey structure with a slack corrugated iron pitched roof and full height plank doors, and two large windows with vertical glazing bars and transoms. There is a flat roofed low single storey extension, part of which has been converted for use as a bus shelter. It is in a poor state of repair, with patchy white render, and joinery in need of repair and a coat of paint. A water tower once stood behind this building.

7.23 Adjacent to the listed George and Dragon pub is a long single storey brick built outbuilding with a pitched slate roof which occupies a prominent position where the view opens up at the road junction (Fig. 28). This building is used as the village stores and post office, facing onto the car park with a long canopy providing protection for goods on display outside. This has what might be described as a modest 'frontier trading post' appearance which is appropriate in this remote location and is relatively unobtrusive and unspoilt by advertising.

7.24 A semi-detached pair of weatherboarded cottages, nos 1-2 Churchend, now barely visible behind trees and scrub, formed part of the 1920s redevelopment. The appearance of these cottages reinforces the distinctive local architecture of the village with their white and black weatherboard elevations and simple design. The positioning also reflects a more historic feature of the settlement. They were built on the site of a single-storey cottage that housed the island's Government agent, which was said to be of Dutch origin. This would have been one of a number of buildings on the island that exhibited the influence of Dutch settlers in the 17th century, and may have been the house referred to in the RCHME inventory of 192313.

7.25 Adjacent to Kents Cottages is a pair of semi-detached two-storey black weatherboard cottages at nos 7-8 Churchend, undertstood to be part of the 1920s redevelopment (Fig. 29). These cottages have a hipped roof of plain clay tiles with a central brick chimney. The windows are flush to the front and are of a modern glazing pattern. Although the front elevation is rather blank, with its simple glazing pattern and lack of elevational detail, these cottages provide a pleasing visual contrast with the adjacent white terrace and the brick cottages to the north.

7.26 Near the site of the old windmill is a single storey cottage, no. 4a Churchend, predominantly finished in black weatherboard but with rendered gables with applied false timbers and white bargeboards, and clay tiled roof (Fig. 30). It is a distinctive and atypical building in the streetscape, but its large open plot and quirky appearance adds interest to the scene. Although essentially 20th century in appearance, its original date of construction is unclear, and it is believed to have developed from an older cottage possibly associated with the old windmill nearby. An old timber shed in the grounds of the cottage is thought to be one of the mill's outbuildings.

7.27 Amongst the 1920s redevelopment are brick semi-detached and detached cottages, numbers 15 to 18 Churchend, built to the north of Kents Cottages to provide homes for the district nurse and policeman (Fig. 31). These two storey buildings are constructed of pale stock brick, laid in stretcher bond indicating modern cavity wall construction, with hipped slate roofs. They mostly have eight over eight sliding sash windows and where original doors have survived they are part-glazed timber construction with small panes reflecting the window glazing. The doors typically have flat canopies on moulded brackets. No.19 Churchend is a detached property of this design but with a single storey side extension with a pitched roof of a corrugated material, full height boarded doors and small paned casement windows (Fig. 32). This was formerly the blacksmith's cottage with adjacent workshop.

7.28 At the southern extremity of the village are numbers 20 to 32 Churchend, cottages constructed during the 1920s redevelopment which are typically two storey semi-detached white weatherboarded cottages, painted black to the side elevations (although there is one single storey property) (Fig. 33). They have hipped slate roofs to the east side of the road, and hipped clay tiled roofs to the west, with central chimneys. Those on the west side have been re-roofed with uncambered machine-made tiles which give a flat, uniform appearance, lacking the texture of older handmade clay tiles. Entrances are to the side with shallow mono-pitched porches that were historically roofed with weatherboard, with the lower portions boarded and solid doors. There is now some variety in the form of these porches, some having been closed in, but they are still typically mono-pitched, small and discrete. There is a consistent pattern of fenestration that provides cohesion to the group, with side casements and a central plain window with top vent. Historic photos show small paned casements on some of these properties, suggesting these are later replacements. At least one original outbuilding survives in this group, at no. 28 Churchend, probably a privy, with a weatherboarded exterior and handmade clay tiles (Fig. 34). This should be retained as these outbuildings generally seem to have been lost. Care needs to be taken that incremental changes to boundary treatments, as well as introduction of garages, hardstanding and other outbuildings in the large plots do not undermine the cohesion of the group and the rural character of the village.

7.29 On the west side of the spinal road there is a historic K6 telephone box adjacent other street furniture relating to various utilities (Fig. 35).

7.30 A more distinctive building that formed part of the 1920s building programme is a long single storey structure at right angles to the road (Fig. 36), of yellow local stock brick with shallow brick buttresses to the sides elevations and corners, full height plank doors to the side, a pitched corrugated roof with small pendant finials at the gable ends and a round window at the gable. This building is what remains of a maintenance yard built for the Royal Engineers, and included an office, carpenters' yard and builders' yard. It is now used by QinetiQ as an estate office. Its brickwork clearly associates it with the domestic dwellings built to the south at the same time, and therefore it forms part of a distinctive group that contributes to the local character of the village.

7.31 Churchfield Cottages are of 1920s or later construction, with yellow stock brick in stretcher bond and pitched roofs of modern machine-made plain tiles or pantiles (Fig. 37). The windows are UPVC with a horizontal emphasis in a simple glazing pattern with plain side-hung casements with top vents. Some have recessed glazed UPVC doors with side lights, or there are side entrances under mono-pitched tiled porches. Although modern in appearance, the use of yellow brick and the scale and simplicity of design of these properties suits the area well, and the generous gardens contribute to the spacious character of the area. Nos 1-2 Churchfield Cottages has a summer roosting population of long-eared bats which is a consideration when undertaking repairs to the building.

7.32 To the rear of Churchfield Cottages and accessed by a track from the road are a pair of semi-detached white rendered single storey properties, built during WWII to provide accommodation for workers at a top secret military installation, the remains of which lie in fields just outside the conservation area (Fig. 38). These properties have been much altered with modern interlocking tiled roofs and replacement windows and doors, and have a rather untidy boundary. Although a track passes in front of the cottages around the field edge, they are barely visible from the public road or public footpaths and can only be glimpsed from the village green, so they do not directly contribute to the street scene. However these distinctive properties are a reminder that this quiet rural village owes much to the military operations across the island.

7.33 Of the main farm complex at Old Hall Farm little remains of what appears on historic maps as a three-sided courtyard arrangement. However one long single storey brick range has survived, now dominated by large modern agricultural sheds (Fig. 39). The fabric of this building includes early soft red brick perhaps of 18th century date as well as the local yellow stock brick introduced in the mid-19th century. The building has a corrugated roof, with raised parapets at the gable ends and full height boarded doors. This structure is a valuable element in the streetscape both in its use of local materials (there is only a limited survival of early local red brick) and also as a reminder of the continuity of historic farming that has been an important feature of the settlement for centuries.

7.34 Tucked behind the bus shelter is a scrubby mound with grand but overgrown steps rising to its summit, where there is an iron pillar gauge (Fig. 40). This is what remains of waterworks believed to date from around 1886, which included a pumping plant and associated water tower14. The introduction of a fresh water supply to the island was an important feature of the Victorian improvements that provided a regular local supply of fresh water. The grandeur of this feature is indicative of the importance of the development to the welfare of the islanders, but it is now in a state of romantic decay. It would be a pity to see this feature lost to encroaching scrub and neglect.

Contribution of greenery and green spaces

7.35 The conservation area is green and spacious, as can be seen from an aerial photo of the village (42). In addition to the contribution of the surrounding landscape setting, trees, open green spaces and gardens make an essential contribution to the special character throughout the conservation area. Domestic gardens are important, with properties typically set in large plots with gardens that are often well planted, aided by the excellent quality of the soil. Hedges often form the front boundaries of properties, enhancing the green and rural character of the village. The village green is an expansive green open space at the heart of the community which is a valuable amenity area. There is also an enclosed grassed play area to the south of the village that provides a safe environment for children. The churchyard provides further extensive green space within the conservation area which has been extended westwards in recent years.

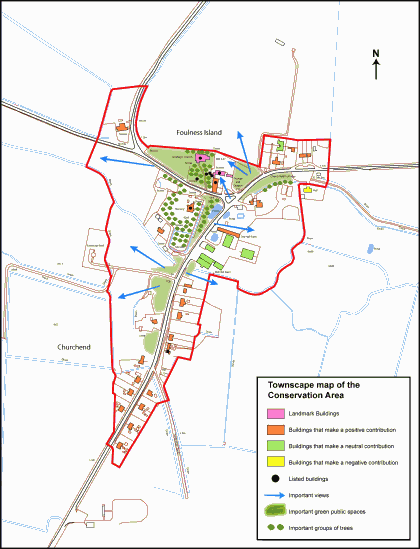

7.36 Generally mature trees and groups of trees are rare on the island, but in the conservation area trees figure prominently providing added landscape value. The map (Fig. 43) attempts to note the contribution of key groups of trees, although trees and tall scrub are characteristic throughout the area. The grounds around the rectory are well wooded. Trees encroach on the green verge along the spinal road opposite the farm, almost obscuring the white weatherboarded cottages at nos 1 and 2 Churchend. There are mature trees in the historic portion of the churchyard, and also along the route of the old byway where it curves eastwards opposite the village green, possibly associated with the former grounds of the Old Hall. There are also trees to the north of the farm which contribute to the street scene around the road junction. The verges are often planted with trees, to the credit of past planting schemes by the MoD.

7.37 There are wide green verges often planted with trees, as along the route of the old byway where the road turns east. These verges are an important feature that contributes to the spacious and verdant character of the area. In places the verges merge into the green or agricultural open space of the surrounding landscape, notably opposite nos 15-18 Churchend. Here the grassy open space is crossed by historic ditches, like the 'Stinking Ditch' (so named because the outflow from the modern flush toilets in the new 1920s brick houses went into it)15. The area also encompasses the site of what were once known as the Round Gardens. There is no evidence of this feature today, the earthwork features having been ploughed out relatively recently, but the gardens are shown on old OS maps and are still remembered within the community. More research is needed to understand the significance of these historic features.

Fig. 43 Townscape analysis map of conservation area.

Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey® on behalf of the Controller of Her majesty's Stationery Office. ©Crown Copyright. Licence number LA100019602

Problems and Pressures

Maintenance

7.38 In the main properties appear to be in a reasonable state of repair and well maintained, but there are some exceptions. These include the agricultural outbuilding near the Old Hall, which is a prominent feature in the streetscape, and perhaps suffers from a lack of useful purpose (apart from as a bus shelter!). The patchy render and rotten joinery create a neglected appearance that detracts from the street scene. The rear elevation of the George and Dragon, which is clearly visible from the village green is also a little neglected. The village hall, although excluded from the conservation area, is highly visible from the public highway and its run-down state intrudes on the character of the area (Fig. 44). The building is a late 1960s low rectangular structure with a flat roof, and a lower flat roofed front extension with a glazed entrance and a horizontal arrangement of windows at a high level. It is rendered in part with timber cladding, and the timber joinery of the windows and doors is in a poor state. The surrounding plot opens directly onto the gravel parking area to the front and is unkempt and overgrown.

Loss of original features

7.39 In the past repairs and upgrades of properties have resulted in loss of original features and some unsympathetic alterations, particularly with regard to replacement windows (Fig. 45). Historic fenestration makes an important contribution to the character of individual buildings and to the overall character and appearance of the conservation area. Other examples of inappropriate modernisation include replacement of historic doors and roofing materials.

7.40 Generally the public realm is well maintained, and is tidy, rubbish-free and unvandalised. However the street scene is marred by a proliferation of street signs, street furniture and road markings, much of which derives from rather heavy-handed traffic management. This creates a cluttered appearance that detracts from the unspoilt rural character of the village. This is particularly evident around the road junction opposite the village green (Fig. 47). As well as the high level of clutter, the design of the street signs and furniture fails to take into account the historic character of the setting. Street lighting is out of scale with the village context. The low metal crash barrier where the road turns eastwards is a particularly poor example that fails to respect the character of the area (Fig. 46). A low modern wall of bright red hard brick at the edge of the pedestrian footpath is also an overly harsh feature. Recycling bins in the gravel carpark at the front of the village hall are unsightly but perhaps unavoidable, although they could be shielded from view.

Access

7.41 Access onto the island is severely restricted and controlled by QinetiQ on behalf of the MoD. The island is a site of great historical and landscape interest, and is an internationally important nature conservation site. It is crossed by many public rights of way but additional byelaw controls mean that these are not always accessible to the public and some are no longer maintained. The restrictions on access and movement around the island mean that these valuable assets cannot be fully enjoyed by the wider public. Visitors to the island can boost the local economy, but business at the George and Dragon pub is an example of a local business that has suffered from these restrictions. There are signs that QinetiQ are relaxing restrictions, with an increase in the number of open days and public events, as well as monthly access to the heritage centre.

Population

7.42 There is a long term question of the future of the community on the island, as the population is declining and is currently at its lowest for well over 200 years. Community facilities are gradually being lost, with the closure of the school and gradual loss of pubs and shops. This has led to some pressure for change of use, which has so far been achieved sympathetically as in the case of the school which has been successfully adapted for use as a heritage centre. This heritage centre has become a valuable resource for the community and a means of preserving the collective memory of the dwindling population of islanders, as well as attracting visitors. Attendance at church services has declined to around 10, creating uncertainty for the future use of the church. The small size of the population and restricted access onto the island has some benefits, including reducing traffic and avoiding pressure for new development, but further loss of community could result in empty properties and poor maintenance. Equally any increase in the population would result in greater pressure for development and new facilities.

12 The History of Rochford Hundred: Foulness, 1867, 205

13 RCHME An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in EssexIV, 47

14 See Dalton, 'Wells on Fowlness Island, Ancient and Modern', The Essex Naturalist, vol. xv, 1907-8

15 See Dobson, pp 24-5