Foulness Churchend Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan

6. Origins and Development

6.1 A wealth of archaeological features and deposits has been recorded from Foulness Island suggesting occupation at an early date. There is evidence of Romano-British settlement and burial, including the Scheduled Ancient Monument site at Little Shelford which produced Roman Coarseware pottery and human remains. A number of 'red hills', salt production sites likely to be of Iron Age or Roman date, are known and are concentrated on the marshland and inter-tidal inlets, and there have been pottery and other archaeological finds dating from the Roman period.3

6.2 The island was first embanked against inundation from the sea sometime in the 13th century, rendering the island more habitable by the medieval period. Until the mid-16th century when the island became a separate ecclesiastical parish Foulness was shared by the mainland parishes of Sutton, Rochford, Shopland, Little Stambridge and Little Wakering. The coastal marshlands provided valuable grazing land for sheep for the distant parishes. These divisions pre-dated the Domesday Survey of 1086, and in common with other areas of Essex coastal marshland that were divided between mainland parishes, Foulness is not mentioned by name in the Survey. The manor of 'Fulness' is first mentioned in 1235, and was one of a number of enclosed marshes each independently protected from the sea by an enclosing wall4. Many of these ancient internal or 'counter' walls with associated ditches that flooded with the tides can still be seen on the island. What is now the village of Churchend lay within the enclosed marsh of South Wick, also known as Foulness Hall Marsh or Old Hall Marsh, within which the manor house stood. The marshes or wicks supported large numbers of sheep which were especially prized as a source of dairy produce - milk, butter and particularly cheeses - as well as for their meat, skins and wool. The number of cattle grazed on the marshland in comparison was relatively small. By the 15th century there was also a considerable amount of arable land within the manor of Foulness, and the sands off the south and east coasts of the island supported an important inshore fishery.

6.3 In addition to the enclosed marshes, successive 'innings' over several centuries reclaimed land from the saltings. The first of these took place in 1420 A.D., and each innings was protected by a newly constructed sea wall. Roads and tracks were sometimes built along the top of these walls, which can still be seen as field boundaries and farm tracks. The final intake took place in 1833. These innings produced highly fertile soils that were ideal for arable cultivation.

6.4 It is likely that the resident population in the medieval period was small, living in scattered shelters, isolated farmsteads and moated sites5. However the population was such that a licence was granted for the building of a chapel on the island in 12836, prior to which residents were expected to attend church in their distant parishes. The exact location of this is not known but it is likely to have been close to the site of the present church at Churchend.

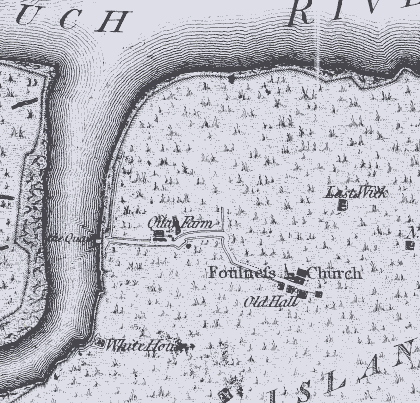

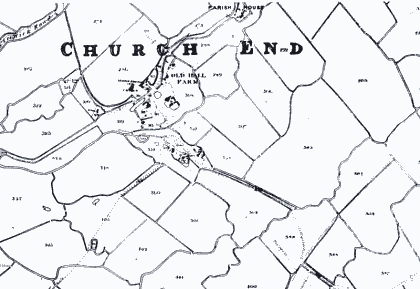

6.5 In the 16th century the population expanded rapidly, perhaps as an increasing proportion of land became devoted to crop growing rather than pasture, requiring a larger labour force. The 17th century witnessed a substantial influx of Dutch settlers, who may have arrived to repair and extend embankments and help reclaim land.The old chantry chapel at Churchend was replaced by a timber-framed parish church dedicated to St Mary the Virgin, Thomas the Martyr and All Saints in the 1540s, located to the south-east of the present church. Settlements were dispersed across the island. Writing in the 1760s Philip Morant describes the houses as standing separately 'for the convenience of occupiers', and as being 'all of wood which soon decay'. There were 19 farms on the island at this time, and the manor house, then known as Foulness Hall, stood near the church7. The dispersed settlement pattern can be seen in the Chapman and André map of 1777 (Fig. 3). This map shows the small settlement around the church and the old hall at Churchend, with properties arranged to the north and south at the end of the roadway leading from the Quay, an important landing point on the river. A cottage built in the 17th century survived close to the church until the early 20th century8. Two cottages to the east of the church had been converted to a public house by the late 17th century, and this survives as the George and Dragon pub. Another roadway leading from the waterside provided a focus for linear development at Cotes End (Courtsend), where the Kings Head received its first Ale House Licence in 1589. Some farmhouses survive scattered across the island from the early post-medieval period, including Ridgemarsh Farmhouse and Priestwood Farmhouse. During the Napoleonic War two semaphore bases were established on the island, manned by the Rochford Hundred Volunteers who were stationed just outside Churchend.

6.6 By the time of the tithe commutation in 1847 there were 4,544 acres of arable land, 783 acres of pasture and 338 acres of inland water including drainage ditches, ponds etc. The remaining 222 acres comprised houses, barns, farmyards, church and churchyard, sea walls and chases, cottages and gardens and waste land9. Up until the mid 19th century, the predominantly male population had a reputation for being rough and lawless, the island providing a refuge for fugitive criminals. Foulness was famous for its bare-fist fighters, and many of the bloody encounters took place in what is now the walled garden in front of the George and Dragon pub.

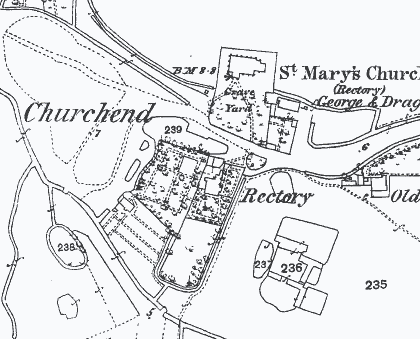

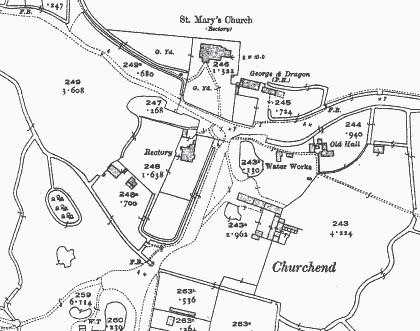

6.7 The population rose steadily during the 19th century, rising from 396 inhabiting 43 houses in 1801, peaking at 754 in 1871 living in 127 houses. Housing conditions in the early part of the century were unhealthy and overcrowded, but there was a marked improvement with the building of new housing over the next few decades. By 1805 a post mill had been erected at Churchend, extending the village southwards with associated buildings that later included the main stores for the island. In 1825 a former pub to the north east of the village became the parish poor house (now demolished). Other new buildings appeared during the 19th century, including a new schoolhouse for 120 children built in1846 north-west of the church. Some of the principal village buildings were rebuilt, including the old manor house, rebuilt around 1850. The church was rebuilt in 1850 in Kentish Ragstone to the designs of William Hambley of London, with extra funds from the Elder Brethren of the Corporation of Trinity House for the addition of a tall spire to signal landfall for mariners. A new rectory was built in 1846. One of the most significant improvements was the discovery that fresh water could be obtained by digging deep boreholes into the ground. Prior to this there was no regular supply of fresh water, much to the detriment of the health of the population. The social and welfare improvements made in the first half of the century were such that in 1867 the historian Philip Benton wrote '... nowadays, thanks partly to the supervision of police and improved tone of morals, the spread of education, a greater care for their souls by their minister, and the spread of religious principles, Foulness is not behind the parishes of the mainland in morality. Crime is now rarely heard of, and a resident policeman is considered unnecessary.'10

6.8 Foulness Island's long association with the military began in 1855 when the War Department established an artillery practice and testing range at South Shoebury overlooking Shoebury Sands, a continuation of Maplin Sands. By the end of the 19th century the decision had been taken to acquire the island and its offshore sands for a weapons development establishment. This involved acquiring the lordship of the manor which comprised about two thirds of the island, as well as purchasing farms outside the manor. By the end of the First World War the whole island was in the hands of the War Department with the exception of a handful of buildings.The island played an important role in weapons testing and research during World War II and the Cold War. A large number WWII military sites remain on the island, including the MoD firing range at Eastwick, heavy anti-craft gun platforms, pillboxes and Nissan huts, as well as post-war installations.

6.9 The island underwent another significant phase of development in the 1920s under the auspices of the War Department, which included demolition of some of the older buildings such as the old windmill. Residents had long contended with the difficulty of access around the island with rough unmade roads and tracks and plank bridges across ditches. There was no bridge from the mainland, and apart from ferries the only route was at low water along the Broomway, a treacherous track across Maplin Sands about a quarter of a mile from the shore. In 1922 the new military road from Great Wakering was opened creating a direct link with the mainland and a route along the spine of the island. The new road in part followed an older byway through Churchend village. A number of brick and weatherboarded cottages were built in the village at this time, some of modern cavity wall construction with flush toilets and baths, extending the village further southwards along the new road.

6.10 Despite the preventive measures taken to protect the island from the sea over the centuries, Foulness still experienced inundations, the worst of which occurred on the night of 31st January 1953 when severe gale-force northerly winds coinciding with a spring tide resulted in the greatest surge ever recorded (Fig. 7). Although the War Department had increased the height of the sea walls, the huge waves whipped up by the wind swept over them, inundating the island. Foulness was left completely cut off from the mainland with neighbouring islands submerged, and telephone, gas and electricity lines broken. Two people died, and 335 were eventually evacuated. In addition, a remarkable rescue operation was carried out under appalling conditions to save hundreds of stricken livestock. The tally of animals eventually evacuated included 400 cattle, 72 sheep, 670 chickens and four budgerigars11. The land eventually recovered from the ill-effects of salt water saturation, and a tree-planting scheme was introduced to replace trees swept away by the flood waters.

Fig. 7 Churchend after the 1953 flood looking north. The church and rectory are marooned in the top left, with Old Hall Farm opposite, its haystacks swept aside by the flood waters. Nos 15-18 Churchend are to the south.

Reproduced with kind permission of R.W. Crump

6.11 In the late 1960s Maplin Sands was considered as a potential site for a third London airport, which would have involved reclamation of 18,000 acres of the sands, but the project was abandoned.

6.12 The island today has a small population of just under 200 people concentrated mainly in the villages of Churchend and Courtsend. It is a close-knit population with a strong sense of community. There are few local services available on the island.

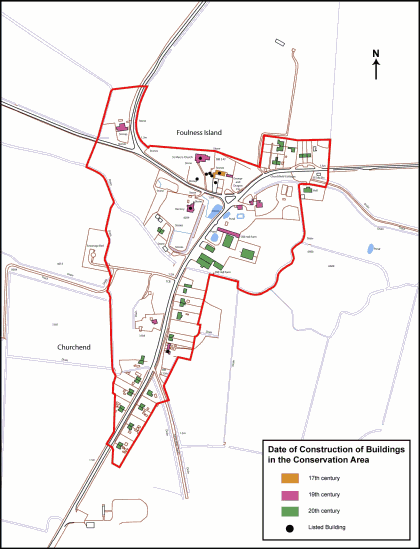

Fig. 8 Date of construction of buildings in the conservation area.

Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey® on behalf of the Controller of Her majesty's Stationery Office. ©Crown Copyright. Licence number LA100019602

3 A summary of known archaeological sites as well as an overview of historic buildings can be found in Appraisal of known archaeological sites and historic buildings for site management statement for the land owned and occupied by Defence, Evaluation and Research Agency (DERA), Foulness Island, a typescript document prepared by Bob Crump in 1998 and available in the EHER. Extensive archaeological survey work has been carried out by the local archaeological society.

4 The name itself derives from two Saxon words, 'fugla' meaning wild birds and 'næss' meaning promontory (Reaney, 1935).

5 There are two earthwork sites within the Churchend conservation area listed in the EHER that may be associated with medieval settlement in the village, including a moat (2796) in the area of Old Hall Farm and an undetermined earthwork south of the present church (2794). See Appendix 2 for map.

6 This is recorded in a document held in Prittlewell Priory Museum.

7 The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex, Philip Morant, 1763-8, 324.

8 This cottage is mentioned in the RCHME Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex4, 47

9 Foulness, J.R. Smith, 1970, 20

10 Benton, The History of Rochford Hundred, Foulness, 1867, 214

11 See Smith, 1970, 33-37