Paglesham Churchend Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan

6. Origins and Development1

6.1 In the Neolithic period Paglesham was situated on the eastern edge of a peninsular of gravel protruding into coastal marsh, just above the high-tide mark. The marsh would have been bisected by numerous small creeks and tidal channels and much of it may have been submerged with each high tide. This attracted prehistoric settlers, providing them with easily tilled soils and access to wetland resources and rich grazing on the marshes. There is evidence for occupation of the area in this period in the form of a jadeite axe found to the south-west of South Hall in 1964. Evidence of Roman settlement is provided by Red Hills, salt production sites located to the north-east of the present settlement at Paglesham.

6.2 The earliest evidence for Saxon occupation in the area is a 6th century brooch. The Domesday book records Paglesham at the end of the Saxon period when there were a total of 20 households and six landowners. The principal land-holding was Paklesham2 or Church Hall manor, which was granted to St Peters, Westminster Abbey by the thane Ingulf in 1066. Writing in 1768, Philip Morant records that in addition to Church Hall there were three further manors in Paglesham, at East Hall, South Hall and West Hall, all named with reference to their location relative to the church3.

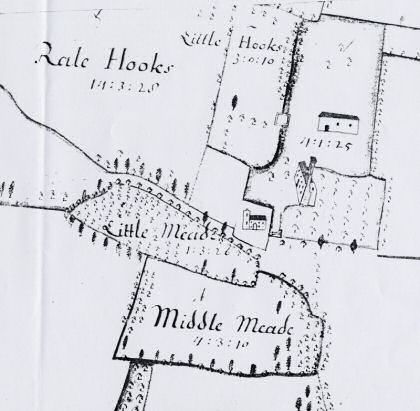

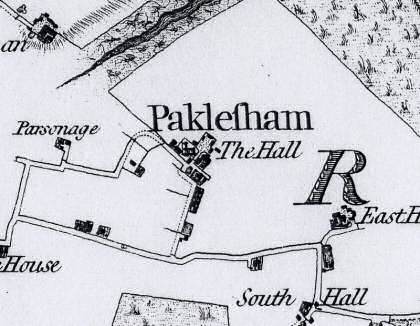

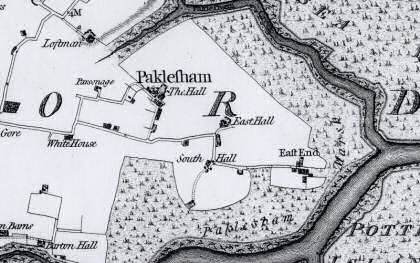

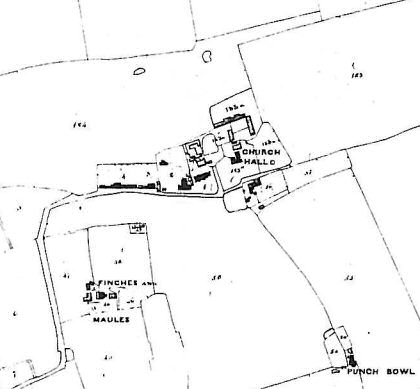

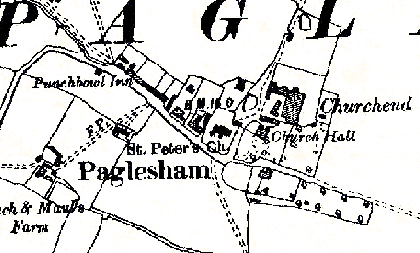

6.3 The medieval settlement of Paglesham consisted of the two hamlets of Church End and East End, with other scattered farmhouses and cottages the more significant of which were moated. The settlement at Church End was a classic church/hall complex, with the hall located to the east of the church (Fig. 3). The Chapman and André map of Essex of 1777 is a good indicator of the distribution of settlement at Paglesham by the end of the medieval period (Fig. 4). At Church End it shows the hall complex east of the church and a larger yard area to the north with six buildings set around the edge (Fig. 5). The medieval rectory was located on the Church End road west of the present settlement, and a pond which closely resembles part of a moated enclosure still exists on the site. In 1473, the manor of Church Hall comprised 200 acres of arable land, 100 acres of saltmarsh (including two marshes on the western part of Wallasea Island), 100 acres of pasture and eight acres of woodland4. In addition to Church Hall, East Hall was located mid-way between Church End and East End within a moated enclosure, with South Hall to the south where traces of what is probably a moated enclosure can still be seen. West Hall, although mentioned in 1475, does not appear on the Chapman and André map, but today there are three attached dwellings on the site with 17th century origins. The existing house of Finches and Moules, sited across fields to the south of Church End, is 15th century in origin, but to the rear is a moated enclosure which presumably marks the location of an earlier dwelling. Paglesham's medieval economy was based on agriculture, particularly sheep-rearing for cheese-making, as well as fishing.

6.4 Paglesham grew slowly in the post-medieval period, and remained a remote and self-contained community. By the end of the 18th century it had gained a reputation for smuggling. One notorious Paglesham smuggler was William Blyth, an important character in local folklore who lived at Church End. He was also churchwarden and village grocer, and was said to have wrapped groceries in pages torn from the parish registers. The small hamlet at Church End grew slightly during this period with new cottages along the road leading to the church, and new farm buildings to the north of the hall (Fig. 6). Although the south side of the church road remained undeveloped, a short row of weatherboarded cottages known as Bedford Row was built in the 19th century across the field from the Punch Bowl. These were demolished in the 1960s. Brick Row was added in the late 19th century. There were more significant developments in the later 19th century at East End precipitated by a prosperous oyster industry. Up until the end of the 19th century much of the River Roach was common ground for oyster fishing, with the remainder divided into private layings. The population of the parish increased slightly from 433 in 1841 peaking at 518 in 1881 after which it slowly declined. Around 200 people lived at Church End in the 1880s, where agricultural labouring was the main form of employment, whilst at East End there were more oystermen. However a wide range of trades were represented in the parish as a whole including cobblers, blacksmiths, bakers, thatchers, carpenters and a range of professions associated with the coastal location including boat builders and ships carpenters.

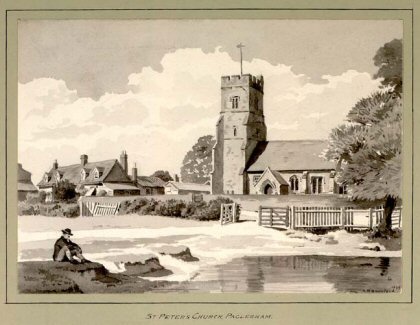

Fig. 7 Church End, c.1899 ( ERO I/Ba 51/1).

6.5 Today the population of Paglesham parish is a little over half what it was a century ago at around 250, living in 100 households. Farming continues to be an important element in the local economy, but the oyster industry has disappeared and boat building is limited to pleasure craft. At Church End, there has been some loss and redevelopment of older properties in the post-war period, including the building of Punch Bowl Cottages in the 1960s and the replacement of the row of tenements at Winton Haw with a large detached house. The most obvious modern interventions are the large industrial farm buildings to the north of Church Hall. In common with East End, Church End has lost its shops and post office. Despite its isolated location and poor local facilities, Paglesham is a well-established, friendly community, with active local organisations including the Village Produce Association and Women's Institute.

Fig. 9 Church End, c.1910.

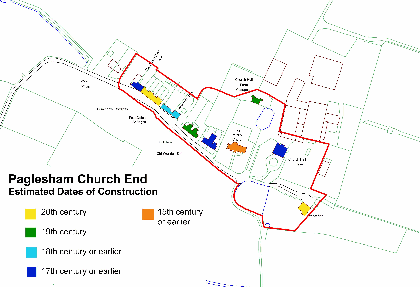

Fig. 10 Estimated dates of construction of buildings in the conservation area.

Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey® on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ©Crown Copyright. Licence number LA100019602

1 See Medlycott, M. 2003 Paglesham Historic Settlement Assessment, Chelmsford: Essex County Council/Rochford District Council. Also Rochford District Council/Essex County Council Rochford District Historic Environment Characterisation Project, 2005. Local historian Rosemary Roberts has written a number of publications on different aspects of the history of Paglesham.

2 The name has Saxon origins meaning the ham (homestead) or hamm (enclosure) of Pæccel. See P.H. Reaney, 1935 The Place-names of Essex, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

3Morant, 1768 The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex, London.

4Benton 1888 The History of Rochford Hundred, Paglesham, Rochford: A Harrington, p. 403.